“What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

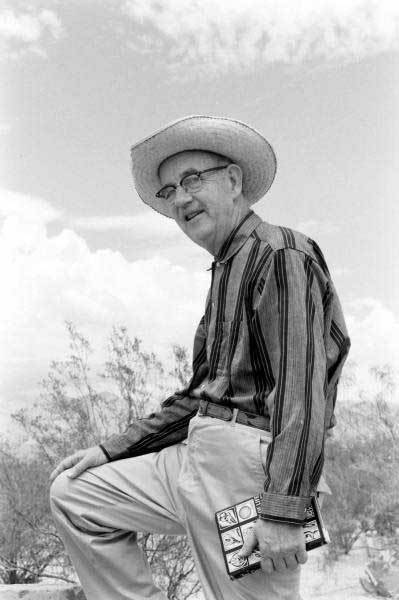

“As I traveled, talking about these issues, I met so many young people who had lost hope,” Jane Goodall told CNN in 2005. The great British primatologist, ethologist, and anthropologist spent her life working with and on behalf of chimpanzees, but now she was concerned about the young adults she was meeting. “Some were depressed; some were apathetic; some were angry and violent. And when I talked to them, they all more or less felt this way because we had compromised their future and the world of tomorrow was not going to sustain their great-grandchildren.”

“As I traveled, talking about these issues, I met so many young people who had lost hope,” Jane Goodall told CNN in 2005. The great British primatologist, ethologist, and anthropologist spent her life working with and on behalf of chimpanzees, but now she was concerned about the young adults she was meeting. “Some were depressed; some were apathetic; some were angry and violent. And when I talked to them, they all more or less felt this way because we had compromised their future and the world of tomorrow was not going to sustain their great-grandchildren.”

It’s easy for children to grow disheartened and disillusioned as they become increasingly aware of the daunting challenges facing our planet. That’s why it’s critical that children learn about environmental heroes like Jane Goodall — people who have dedicated their lives to scientific observation and preserving what little natural habitat remains. But Jane Goodall is much more than a scientist and environmentalist. She’s also a stellar example for young women and, as an individual with strong convictions who practices what she preaches, she’s a role model for all of us.

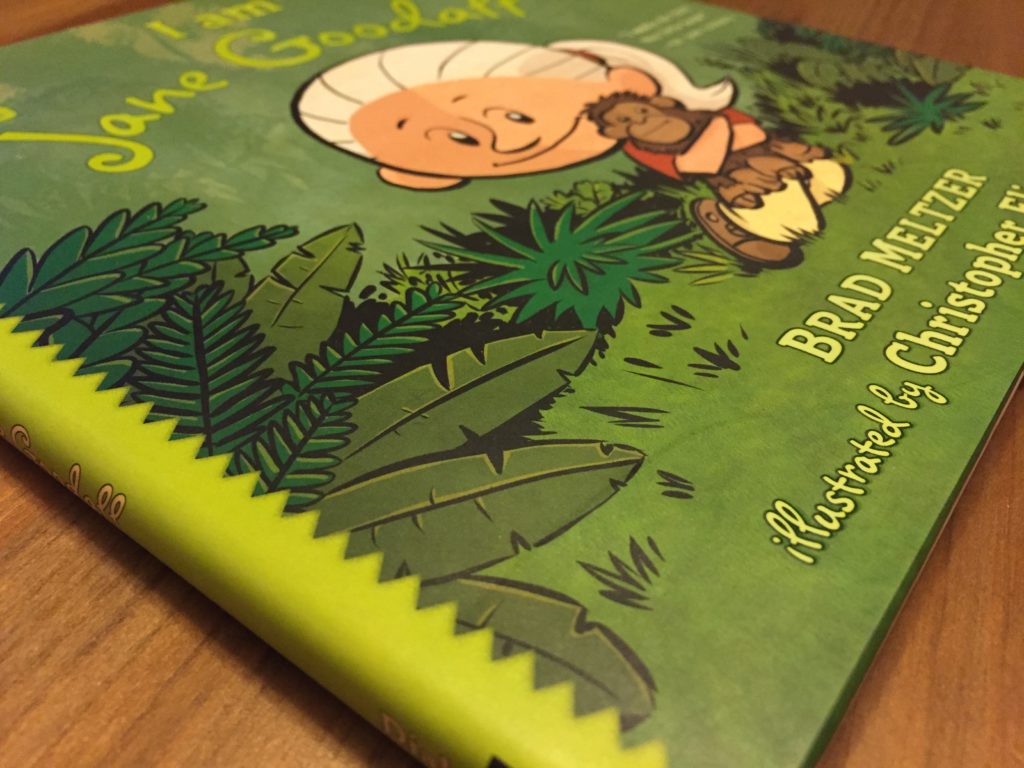

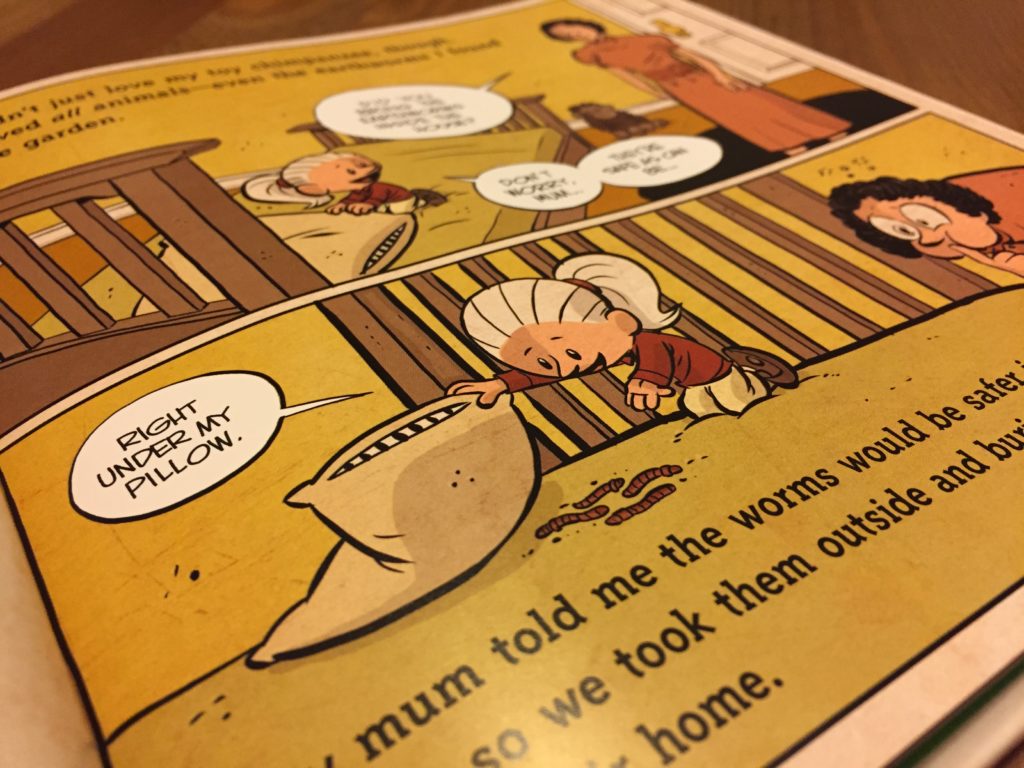

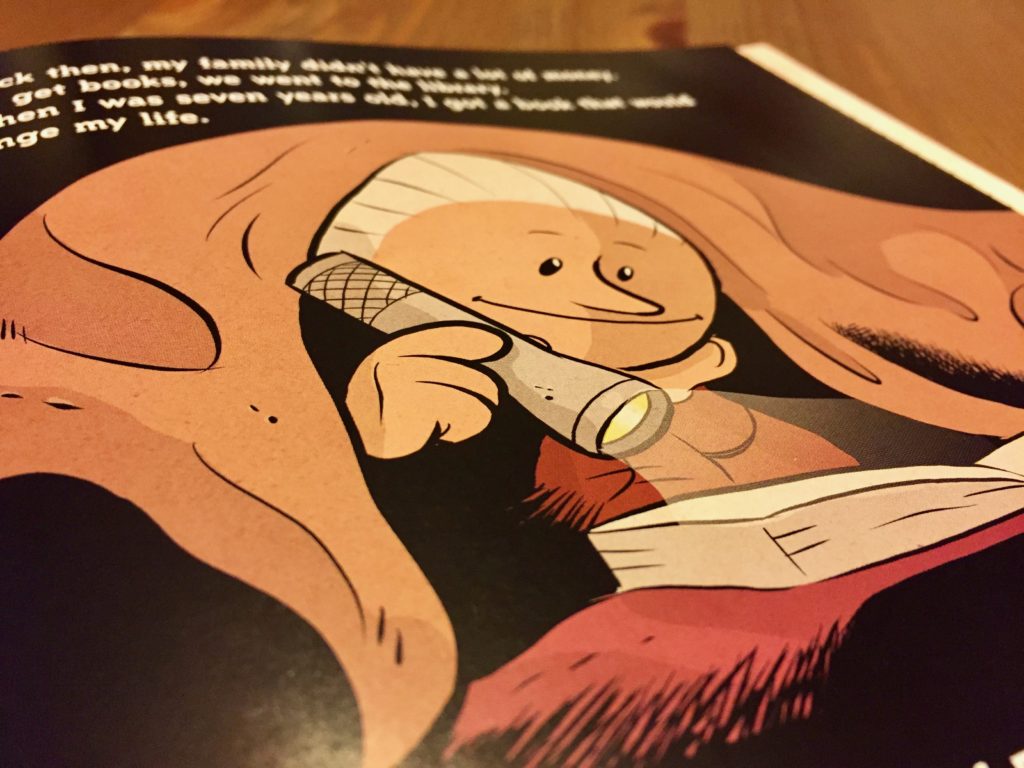

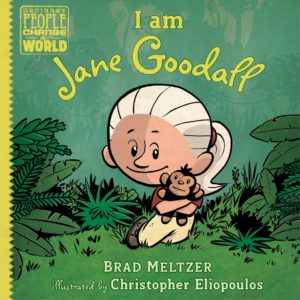

Now there’s an easy way to share Jane Goodall’s life story and philosophy with children. I Am Jane Goodall (public library) is a children’s book written by Brad Meltzer and illustrated by Christopher Eliopoulos that summarizes Jane Goodall’s life in about 40 pages. The story is based on Jane Goodall’s own books and written in first-person narration. With eye-catching, comic book-style illustrations and lots of thought bubbles, the book is perfect for kids ages 5-12.

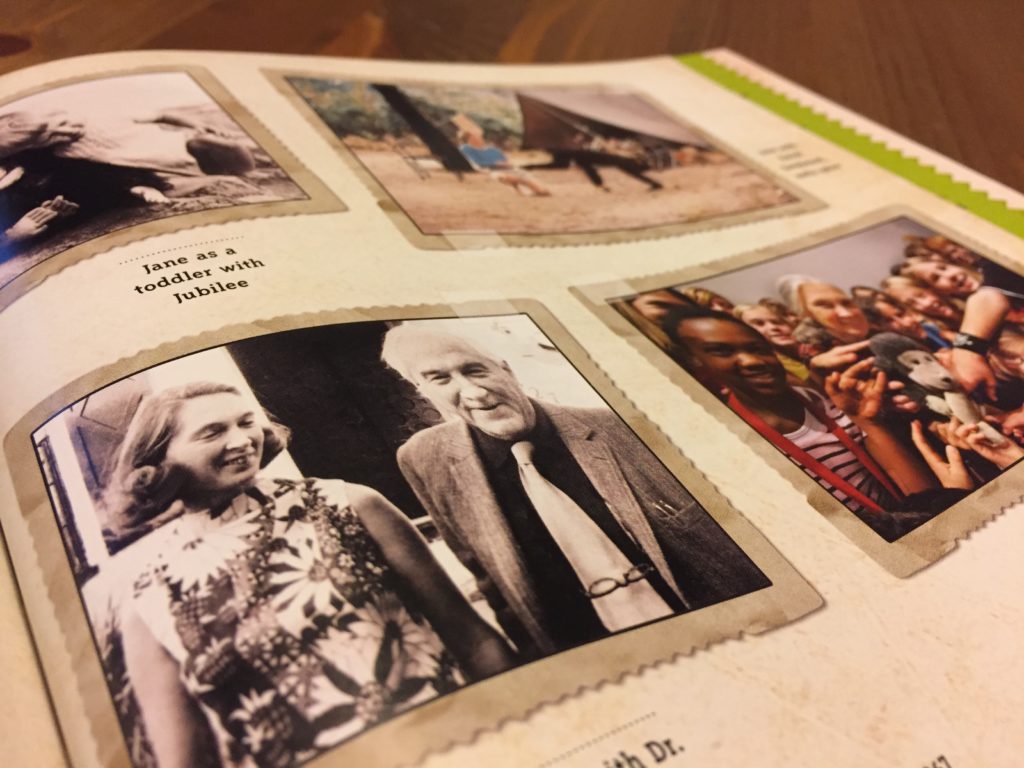

The story starts by recounting several specific events from Jane Goodall’s younger years.

I wanted a job where I learn more about animals. But back then, if you were a girl, people didn’t think you could become a scientist. They expected girls to become nurses, secretaries, or teachers.

I wanted to go to Africa. I wanted to study animals. Luckily, my mom always told me: ‘If you really want something, work hard for it. If you don’t give up, you’ll find a way.’

I never forgot that.

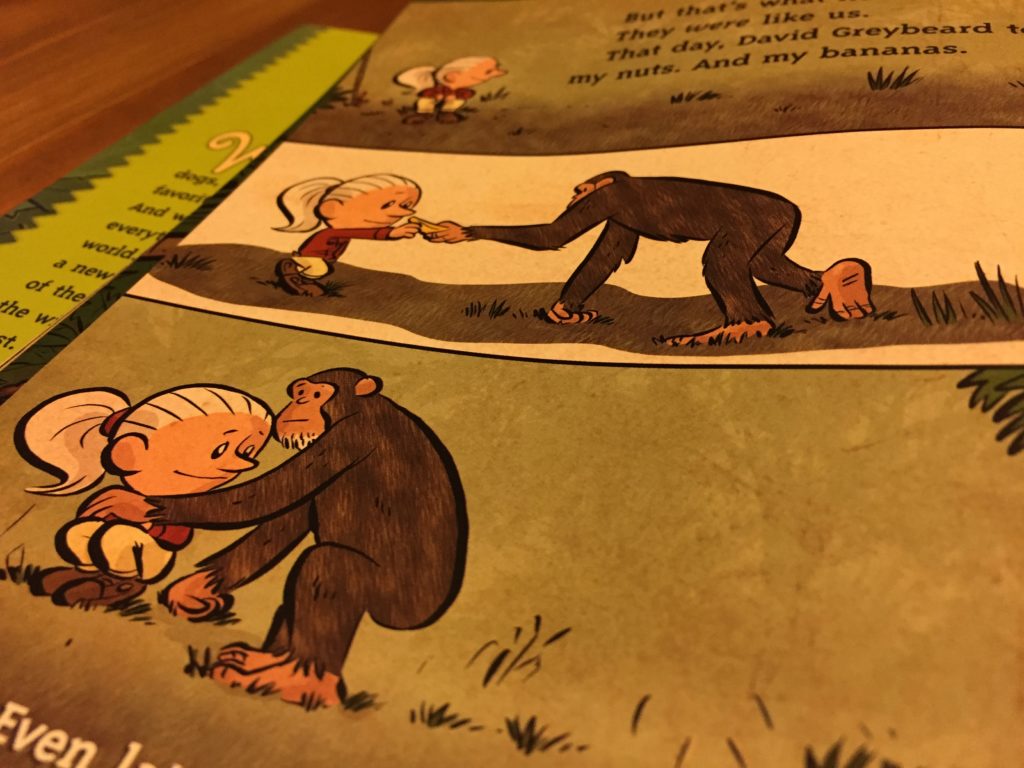

As you might imagine, the majority of the story is focused on Jane Goodall’s adult years and the time she spent researching chimpanzees. It’s a beautifully concise summary that accurately captures the highlights of Jane Goodall’s life in Africa. In many ways, the best part of the story comes near the end of the book, when a moral is drawn from the lessons Jane Goodall learned along the way. It’s an uplifting message that provides concrete advice for young people.

In my life, people told me there was a ‘certain way’ to do things: a ‘certain way’ to study animals, a ‘certain way’ that girls should behave. They told me to follow the rules. Instead, I followed my gut.

In your life, it will be easy to see how others are ‘different’ from you. But there’s so much more to gain if you instead see how alike we all are. All of us — all living things — share so much. We have so many things in common.

Watch. Observe. Be patient. It’ll teach you this: We don’t own this Earth. We share it.

Listen to the feelings in your heart. We are responsible for the animals around us. We must take care of them. When one of us is in trouble — be it human, creature, or nature itself — we must reach out and help. When we do, we build a bridge… a bridge that will carry all of us.

The book is one in a series entitled “ordinary people change the world,” a description that certainly seems to fit Jane Goodall. As a child, she had a dream. As an adult, she followed it — to great success.

Children can learn a lot from the example set by Jane Goodall. As she’s quoted saying at the end of the book, “You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

To that end, Jane Goodall founded the Roots & Shoots program in 1991. It’s a network of more than 150,000 groups of young people who share a desire to create a better world. Young people identify problems in their communities and take action through service projects and youth-led campaigns. Please join us in making a donation.

I Am Jane Goodall is a must-read book for kids concerned with the environment, girls in need of a strong role model, and children who like reading about successful people who have changed our world for the better. Complement with A Little Bit of Dirt, a book with over 50 science and art activities for children, then revisit Mossy, a beloved children’s book by Jan Brett about a turtle plucked from her native habitat and put on display in a museum.