“I think the best parents and guardians show their kids how to see the beautiful. And part of that is helping those who have even less.”

“The question is not what you look at, but what you see,” Henry David Thoreau wrote in his journal on August 5, 1851. In this modern age of distraction, it’s all too easy to ignore things that initially appear ugly and unusual—to lose, as the great anthropologist Loren Eiseley so elegantly put it, our “sense of awe.” Of course, the hidden beauty is still there, just waiting to be discovered. All we have to do is open our eyes and trust our senses. This is one of the central themes in Last Stop on Market Street (public library), a stunning work of children’s literature by author Matt de la Peña and illustrator Christian Robinson that is guaranteed to be treasured for generations to come.

“The question is not what you look at, but what you see,” Henry David Thoreau wrote in his journal on August 5, 1851. In this modern age of distraction, it’s all too easy to ignore things that initially appear ugly and unusual—to lose, as the great anthropologist Loren Eiseley so elegantly put it, our “sense of awe.” Of course, the hidden beauty is still there, just waiting to be discovered. All we have to do is open our eyes and trust our senses. This is one of the central themes in Last Stop on Market Street (public library), a stunning work of children’s literature by author Matt de la Peña and illustrator Christian Robinson that is guaranteed to be treasured for generations to come.

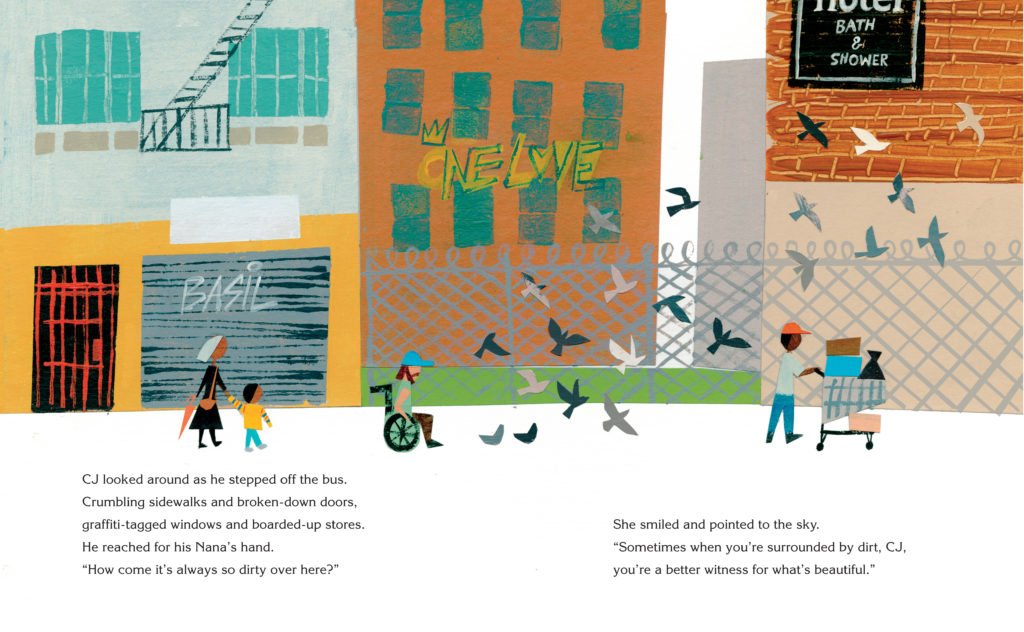

The story begins when CJ, the African-American hero of the story, leaves church with his grandmother (“Nana”). The duo take a bus ride through the inner city to a soup kitchen where they serve food to the homeless. Along the way, CJ peppers Nana with difficult questions about why things are the way they are for their family, community, and city. (“Nana, how come we don’t got a car?”) Nana’s wise and witty responses provide CJ and readers with an unforgettable lesson in empathy, patience, and learning to see beauty where others see only ugliness.

Diversity is a hallmark of this story, but it’s not the overriding theme. According to author Matt de la Peña, that’s by design.

It’s a book that features diverse characters that has nothing to do with diversity. My dream is for a book like this to be embraced not just by diverse readers, but all readers. The story is universal even if the characters are specific.

Readers will notice that disabled and disadvantaged people are interwoven with the story — a blind man, an individual in a wheelchair, a man pushing a shopping cart. It’s an accurate portrayal of the people present in urban environments, and a refreshing change from the majority of modern children’s literature. The dialogue regarding these people feels completely natural.

A man climbed aboard with a spotted dog. CJ gave up his seat. ‘How come that man can’t see?’

‘Boy, what do you know about seeing?’ Nana told him. ‘Some people watch the world with their ears.’

Inequality is also quietly acknowledged throughout the story. On more than one occasion, CJ asks Nana why they don’t have something. Instead of lamenting the absence of physical possessions, Nana redirects CJ’s attention to what they do have. Nana’s continuous focus on her immediate surroundings is a powerful reminder that those who don’t have much may have something better — a deeper appreciation of the present. As De la Peña eloquently put it, “I think the best parents and guardians show their kids how to see the beautiful. And part of that is helping those who have even less.”

De la Peña is no stranger to the world of the underprivileged. As a child growing up in New York City, he had no money and few prospects for the future. In an interview, De la Peña stated that he is fascinated by the stories of underprivileged children, and that all of his books touch on class issues.

I will always write about kids growing up with less. My own experience with poverty is the single most defining piece of my childhood. If my stories create empathy, great. But that’s not exactly what I’m after. I just think the lives of kids growing up in difficult circumstances are beautiful and worthy, too. Truth is, these kids start the race of life way behind the pack. For me, the most interesting journey to follow is the kid who’s fighting to catch up. Even if he never gets there, his story is still so valid to me. Class is definitely the unspoken part of the diversity equation.

The author and illustrator also have some advice for parents hoping to teach lessons of empathy and diversity. “Reading is the ultimate form of empathy,” says De la Peña. “Kids who are exposed to stories from a young age are more likely to carry empathy in their hearts — without even being aware of it.” Robinson, the illustrator of Last Stop on Market Street, says that “exposure to different kinds of people, cultures and music might help a child be aware of the infinite possibilities of expressing and being oneself.”

De la Peña is an advisor to We Need Diverse Books, a grassroots organization dedicated to putting more books featuring diverse characters into the hands of all children. Please join us in making a donation.

Last Stop on Market Street is a remarkable story full of life lessons that are rarely introduced in other children’s books. Powerful and emotional, this book deserves a spot on every child’s bookshelf. Complement it with other children’s books on diversity.