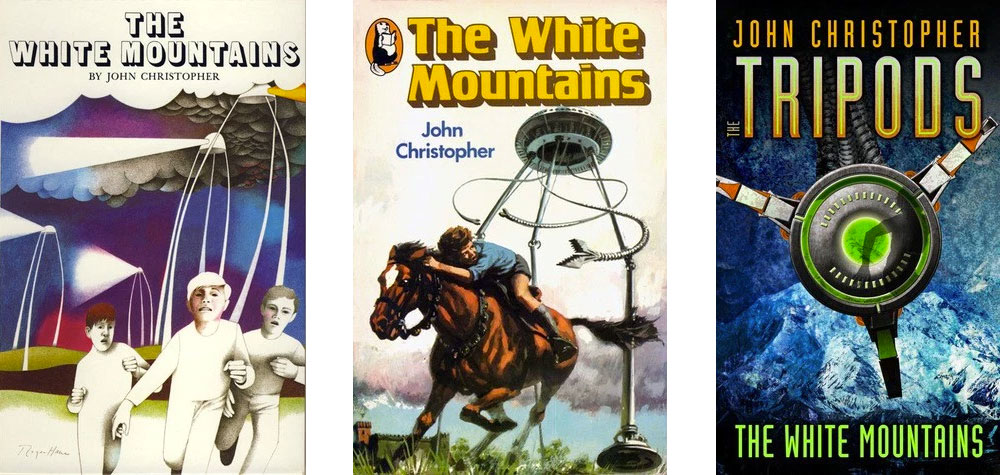

First published nearly 50 years ago, The Tripods series remains one of the very best introductions to young adult science fiction literature.

“Science fiction is the most important literature in the history of the world,” mused beloved author Ray Bradbury. “It’s the history of ideas, the history of our civilization birthing itself.” The deeply creative world of science fiction literature first becomes accessible to children when they turn nine or ten years old. The Tripods (public library) series of books by John Christopher is intensively captivating and easy to read — perfect for introducing kids ages 9-13 to science fiction.

“Science fiction is the most important literature in the history of the world,” mused beloved author Ray Bradbury. “It’s the history of ideas, the history of our civilization birthing itself.” The deeply creative world of science fiction literature first becomes accessible to children when they turn nine or ten years old. The Tripods (public library) series of books by John Christopher is intensively captivating and easy to read — perfect for introducing kids ages 9-13 to science fiction.

The books center around the tripods — giant, sinister machines with three legs that rule the Earth. By installing a cap on each adult’s head, they’re able to control the entire human race through mind control. Everyone, that is, except for a small group of holdouts that quietly wage war on the tripods in the hopes that the planet will one day be free again. The renegades concentrate on recruiting preteens who haven’t yet been “capped” and who are open to new ideas. Kids create pockets of resistance in this world of brainwashed adults controlled by an evil alien force.

If the premise sounds rebellious and anti-authoritarian, that’s because it is. In an interview, author Sam Youd (whose pen name was John Christopher) suggested that the series appeals to pubescent readers precisely because they themselves view the world suspiciously.

I think the successful children’s books are those which appeal to something at a deeper level which the child doesn’t really quite work out. Now in The White Mountains, the whole thing is that at puberty people are brainwashed. The whole future of mankind rests in the hands of the young, the age group for which I’m writing. I think that kids at that age – around 12 or 13 – probably do look at the adults around them resentfully and think of them as hidebound and prejudiced. It’s important for children to have stories which put them in the driving seat.

The series is a collection of four books: When the Tripods Came (prequel — 1988), The White Mountains (1967), The City of Gold and Lead (1967), and The Pool of Fire (1968). Readers may want to start with the prequel since it lays the groundwork for the original series.

Individuality and free will are strong themes throughout the books. The capped adults have lost all traces of the personality traits that made them unique human beings. Their behavior is flat and tempered, something that terrifies the freethinking narrators of the books.

The Head Man droned on. He was thin and anxious, white-faced and white-haired (what there was of it), due for retirement at the end of the school year. I wondered about being like him, too — just about able to cope under normal conditions, without things like Tripping to contend with.

What I was suddenly aware of was the importance of their being whatever each of them was — cocky and contemptuous, or bothered and beaten — as long as it was something they’d come to in their own way: the importance of being human, in fact. The peace and harmony Uncle Ian and the others claimed to be handing out in fact was death, because without being yourself, an individual, you weren’t really alive.

Readers discover later in the series that the tripods are piloted by aliens who live in dome-covered cites. Soon after arriving on Earth and enslaving everyone, the alien species returned the human race to a preindustrial way of living — one entirely devoid of modern technology. The holdouts living in the mountains make plans to destroy the tripods and free the human race.

There are viewing points where one can look out from the side of the mountain. Sometimes I go to one of these and stare down into the green sunlit valley far below. I can see villages, tiny fields, roads, the pinhead specks of cattle. Life looks warm there, and easy compared with the harshness of rock and ice by which we are surrounded. But I do not envy the valley people their ease.

For it is not quite true to say that we have no luxuries. We have two: freedom, and hope. We live among men whose minds are their own, who do not accept the dominion of the Tripods and who, having endured in patience for long enough, are even now preparing to carry the war to the enemy.

It’s worth noting that the series has been rightfully criticised for its notable absence of female characters as well as some subtle racist references. As one Slate editor put it, “to have found that one of my favorite childhood books was sexist in this casual, negligent way was alarming.” But for parents and readers who can look past these shortcomings, The Tripods series provides nail-biting entertainment. This is science fiction at its best.

The Star Wars and Star Trek franchises get all the publicity, but readers willing to dig a little deeper will discover a treasure trove of wonderful science fiction literature for kids and young adults. First published nearly 50 years ago, The Tripods series has stood the test of time. It remains one of the very best introductions to the world of young adult science fiction literature. Complement with Hoot by Carl Hiaasen, a novel for young adults about middle school students standing up for what they believe in.